Understanding the critical role of food supply chains in hurricane and disaster relief

Table of Contents

The Crisis Within the Crisis

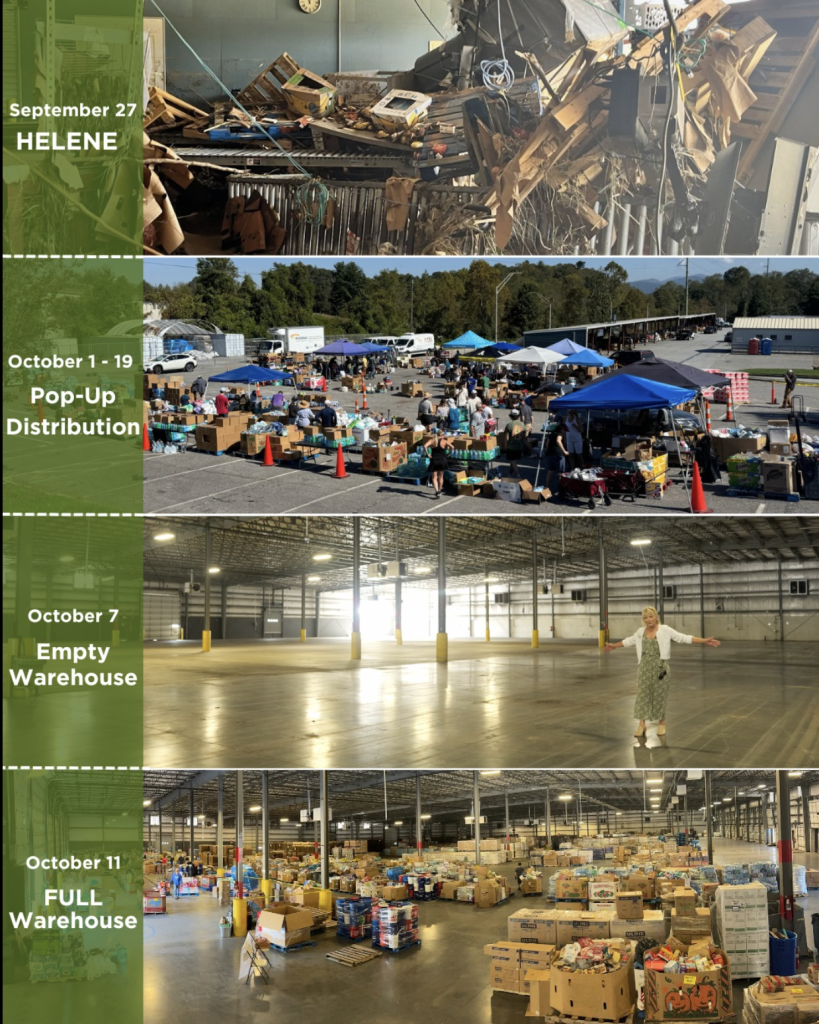

In September 2024, Hurricane Helene’s floodwaters ripped the walls off the MANNA FoodBank in Asheville, North Carolina. Within hours, the primary food distribution hub for Western North Carolina was gone, reduced to open-air parking lot operations with no refrigeration, no permanent shelter, and thousands of additional families suddenly cut off from food access.

But the physical destruction was only the beginning. Kristi Rose was serving in food sourcing at MANNA during Helene. She recalls the moment reality set in: “Communication was really almost non-existent. Our staff couldn’t reach each other due to a complete communication breakdown—no cell service, no internet, no power.

Travel was perilous until some major roads were cleared. It took a couple of days for much of our staff to get anywhere where we could communicate. When I got the email about our building being destroyed, that was one of the first big understandings of the extent of what had just happened.”

In neighboring communities that escaped the flooding, phones started ringing at agencies across the region. Displaced families were streaming into their communities. Local demand was spiking as people who had never needed food assistance found themselves without power and without access to grocery stores. The question wasn’t just how to feed people—it was how to get the right food to the right places when the entire infrastructure had collapsed.

This is the hidden crisis within every disaster: while first responders focus on immediate life safety, communities face a parallel emergency that can persist for months. People need food they can eat without cooking, without electricity, often without clean water. And they need it delivered to places that may no longer exist on any logistics map.

Twenty years after Hurricane Katrina redefined disaster response, and one year after Helene devastated the Carolinas, the lessons learned about emergency food distribution have never been more relevant. As more widespread areas face increasingly severe weather events, understanding how the supply chain makes rapid food relief possible could mean the difference between an organized response and chaos.

The Invisible Network That Saves Lives

Behind every successful disaster food distribution operation is a network most people never see: wholesale food distributors, brokers, manufacturers, and logistics specialists who understand that following a disaster speed means more than efficiency. It means survival.

This network includes specialized companies that understand the hunger relief sector intimately. Unlike general food distributors, some businesses like VAFS work exclusively with nonprofits, with 98% of their revenue coming from hunger relief organizations. This focus creates a deep understanding of food bank operations, nonprofit budgets, and the unique logistical challenges that arise when disaster strikes.

The 72-Hour Window

Emergency management experts know that the first 72 hours are critical. But food relief presents complex logistical challenges: distributing nutrition that people can actually consume when they have no power, no kitchen facilities, and sometimes no access to clean water or proper food storage.

These specifications aren’t theoretical—they’re hard-earned knowledge from more than twenty years of disaster response, lessons learned about what works and what fails when communities lose their infrastructure.

The Supply Chain Race Against Time

When disaster strikes, traditional supply chains collapse. The vendor who normally delivers to a food bank on Tuesday may have a warehouse that’s flooded. The transportation company that handles regular routes may have trucks stranded on impassable roads. The food bank itself may be operating from a parking lot.

This is when the mutual aid relationships built during calm periods become lifelines. Neighboring food bank cooperative agreements kick into gear, enabling unaffected facilities to absorb displaced populations and coordinate emergency distributions. Wholesale food distributors who have worked closely with manufacturers for years can often secure emergency orders with priority status. Companies with their own distribution centers fill important gaps, reducing industry-standard delivery times from months or weeks to days. For instance, Value-Added Food Sales offers year-round five-day delivery time from its own distribution centers. Following a disaster, VAFS can often prioritize and expedite orders for relief work even faster.

During Hurricane Helene, VAFS account managers and warehouse personnel worked around the clock—not just taking orders, but coordinating with their network of 110+ vendors to ensure food kept flowing to affected regions from their regional mixing center in neighboring Charlotte, North Carolina, and other areas of the country from where they could shift supplies rapidly managing supply chains that had to adapt to roads that no longer existed and regional warehouses that were underwater.

From Katrina’s Lessons to Today’s Standards

Hurricane Katrina didn’t just devastate New Orleans—it exposed critical gaps in how America responds to disasters. Even the unprecedented distribution scale of Feeding America and the Red Cross wasn’t enough for the immediate, monumental food purchasing needs that emerged.

When traditional emergency response structures couldn’t meet the demand, organizations that knew the Food Bank community intimately became essential bridges between need and supply. Value-Added Food Sales was already an established business serving hunger relief agencies. Our reputation with food banks across the country led to the Red Cross and Feeding America reaching out to us to help fill the Katrina emergency food void…quickly.

The lessons learned from that response became the foundation for modern disaster relief food standards, and VAFS was proud of the work we contributed to helping develop those new standards.

Organizations had to figure out through trial and error what actually worked when people lost their homes, their kitchens, their surrounding grocery stores, and their basic infrastructure.

The Evolution of Emergency Food Boxes

Today’s disaster relief boxes reflect twenty years of refinement. Relief organizations and companies, including VAFS, involved in post-Katrina relief were part of the initial groups that established industry standards through real-world testing:

- Rice and similar dried items were removed from emergency boxes because they require cooking facilities and water that disaster victims may not have

- Can openers became standard inclusions because displaced families can’t rely on having basic tools

- All foods must be ready-to-eat or consumable cold

- Shelf life must support 6-8 months of storage for emergency preparedness

Two-Phase Response Strategy

Modern disaster relief recognizes two distinct phases of need:

Phase One (Immediate Response): For people with no cooking facilities, no electricity, and sometimes no clean water. Every item must be consumable without preparation.

Phase Two (Temporary Housing): For communities transitioning to temporary housing with basic kitchen access. Traditional pantry boxes with items that require basic food preparation become viable again.

When Everything Disappears: Total Infrastructure Loss

While many food banks have some form of disaster preparedness plans, few plan for the complete destruction of their facilities or their local infrastructure. MANNA FoodBank’s experience reveals critical vulnerabilities that extend far beyond physical buildings.

Technology Infrastructure Matters

MANNA lost more than their facility; they lost their entire inventory management system. “We also lost our inventory system because it was hosted on-premise and not cloud-based. Imagine everything you rely on to do your job and the base of your processes disappearing overnight. Simply navigating all of the food coming in and trying to track it in some way without our inventory system was not something we planned for,” explains Kristi Rose.

“In the immediate aftermath, with no power and no digital systems, tracking became brutally simple: “It was essentially like, we received this many trucks and we served this many people.” It took weeks to transition to a new ERP system, and about a month to conduct a full inventory using bills of lading to estimate what moved through during the crisis period.

Leadership Clarity Amid Chaos

While physical destruction grabbed headlines, MANNA’s response revealed how organizational culture becomes the foundation when everything else disappears. Rather than simply reacting to loss, leadership made strategic decisions that positioned the organization for rapid recovery.

When everything disappears, organizational culture becomes the only stable foundation. MANNA’s CEO immediately sent a message that became their operational philosophy: “MANNA has never been a building. We are—and continue to be—an incredible network of dedicated people who care about our neighbors. We will be here to help those who need us.“

And she backed it by concrete support for the team, many of whom were also experiencing extreme personal loss. “That first month, we all got paid, like, regardless of if you could work, if you couldn’t work,” Rose notes. “Our team was already mission-based, but that understanding and flexibility… went a long way.”

Operational Flexibility Becomes Survival

For the first two weeks post-storm, Helene forced MANNA FoodBank to shift from its traditional model of serving partner agencies to direct community distribution. Operating from the Western North Carolina Farmers Market parking lot, they received donations in the morning and distributed food in the afternoon, eventually handling full semi-trucks in the parking lot. During this initial crisis timeframe, they served over 8,000 families at the farmers market. Once they secured the 99 Broadpointe Drive warehouse facility within those first two weeks, MANNA got their trucks back on the road, delivering critical food, water, and emergency supplies to partner agencies across their 16-county service area in WNC and the Qualla Boundary.

Additionally, staff needed ongoing flexibility for months, not weeks. Schools and daycares remained closed, FEMA appointments and insurance adjusters required meetings during business hours, and contractors needed access to damaged homes. “It would be like, Okay, I can’t work normal hours during the day, but I can work until 11pm at night and get things done then,” Rose recalls.

Lessons from the Front Lines: Inside Hurricane Helene Response

Hurricane Helene’s impact on North Carolina demonstrated how the disaster relief food network has evolved since Katrina. Rather than simply replacing destroyed facilities, the response focused on understanding displacement patterns, surge capacity needs, and the interconnected nature of regional food distribution systems.

The Displacement Effect

When food banks are destroyed, the response cascades through the entire regional network—each remaining facility must absorb displaced populations while also coordinating emergency shipments to affected areas.

VAFS’s Charlotte mixing center, operating in partnership with Second Harvest Food Bank of Metrolina, provided a unique vantage point during Helene’s response. The facility was involved firsthand in helping a major food bank manage surge capacity when neighboring regions lost their entire infrastructure.

Joe McKinney, Director of Food Strategy at Second Harvest Food Bank of Metrolina, lived through Hurricane Helene’s impact firsthand. With their mixing center collocated with VAFS in Salisbury, North Carolina, McKinney had a unique vantage point on both food bank operations and supply chain response during one of the region’s most devastating disasters.

“When Helene hit, it was unlike anything,” McKinney recalls. “I still have unprocessed trauma from it, and I don’t mean to say that jokingly.” The storm didn’t just destroy infrastructure—it tested every assumption about disaster preparedness and revealed the critical importance of relationships built during calm periods.

Acting Before Funding Arrives

One of McKinney’s most crucial insights challenges conventional thinking about disaster response funding: “We had a plan, but it didn’t cover this level of devastation. We didn’t ask… we didn’t make a full strategy to complete the circle on how we could do it. We did it, and we were doing it in large volumes before things even started to look like they would stabilize.”

Second Harvest of Metrolina activated massive purchasing and operations immediately, trusting that donations would follow—which they did. This approach allowed them to respond while other organizations were still assessing needs or waiting for funding authorization. The lesson for other food banks: having financial reserves and leadership willing to act decisively can mean the difference between immediate relief and delayed response.

The Power of Established Relationships

Cooperative relationships and partnerships rippled through the supply chain. Metrolina’s longstanding relationship with MANNA FoodBank in Asheville proved invaluable. “We basically had to pause some of our efforts to address needs in our own community so that we could help our sister food bank,” McKinney explains.

But it wasn’t just food bank relationships that mattered. The partnership with VAFS proved essential: “Their five-day lead time essentially disappeared for use entirely during the immediate response to Helene. It was the same day. There was no five-day lead time at all. It was like minutes.”

VAFS was able to expedite large direct shipment orders placed with manufacturers and orders to restock their own mixing center location due to the long-standing relationships VAFS maintains with manufacturers.

This operational flexibility, made possible by established partnerships, allowed for an immediate response when every hour counted.

Dual-Prong Mutual Aid: Local and National

Effective mutual aid operates on two levels simultaneously. For MANNA, the closest food banks became “ad hoc team members,” as Kristi Rose describes it. Joe McKinney and Aaron, his counterpart from Central & Eastern North Carolina (Raleigh, NC), would text Rose directly: “Here are the items available. Do you want them? Yes or no, I’ll arrange transport.” These peer-to-peer relationships enabled MANNA to mount an immediate and flexible response.

Simultaneously, Feeding America coordinated national support, assigning supply chain specialists to streamline donation offers from across the country. “Instead of all of those in-kind donations coming from 50 different food banks around the country,” Rose explains,” this provided ‘one source’ for coordinating larger in-kind donations from distant locations.”

Stock for Speed, Rotate for Efficiency

McKinney strongly supports the five-day inventory strategy for emergency preparedness, with a practical twist: “Having stock on hand for immediate response buys you time to start your response plan.” His recommendation goes beyond just stocking disaster supplies—create systems to rotate emergency inventory through regular operations.

“We distribute [unused disaster supplies] to food banks that may likely have gotten them anyway,” McKinney notes. This rotation prevents waste while maintaining readiness. If our relief supplies go unused during hurricane season, these boxes simply flow into normal distribution channels.

Scale and Duration Will Surprise You

The scale of Helene’s response exceeded all planning assumptions. Second Harvest Food Bank of Metrolina ordered 95,000 cases in October 2024—a 41% increase over normal operations. They set up mass packing operations at Charlotte’s convention center, coordinating corporate volunteers, National Guard personnel, and healthcare workers to pack thousands of boxes above their normal capacity weekly.

“It was so far above what we would typically call a busy day,” McKinney reflects. “And you know, it was chaotic.”

Make Disaster Plans Real, Not Performative

McKinney’s strongest recommendation focuses on preparation authenticity: “Having a strategic disaster relief plan is highly critical… but we’ve made sure that it is actually more than just something to satisfy an obligation. It’s real.”

His specific recommendations for food banks:

Establish a Disaster Relief Committee: Designate one person from each department—transportation, warehousing, development, agency services—who are pre-assigned for crisis response. “When stuff hits the fan, they already are the ones. You don’t have to figure out who is on deck.”

Develop Real Mutual Aid Agreements: Go beyond informal relationships to structured agreements with neighboring food banks, local partners, vendors, trucking companies, and alternative facility locations, such as convention centers.

Plan for Sustained Operations: The response has lasted months, not weeks, testing staff endurance and organizational capacity in ways no plan had anticipated. Develop plans that assume extended operations, not just immediate response.

Building Resilient Disaster Response: Strategic Preparedness

The Five-Day Inventory Strategy

One of the most practical insights from two decades of disaster response is the “five-day rule”: food banks in disaster-prone areas should maintain at least five days’ worth of emergency inventory on hand, as that’s how long it takes to receive new supplies often even with expedited processing.

The math is simple but critical: if a supplier can fulfill emergency orders in five days (compared to the industry standard of 2-3 weeks), food banks need just enough inventory to bridge that gap. This prevents both under-preparedness and the waste that comes from over-stocking perishable items.

Beyond Major Disasters: Individual Emergencies

Emergency food boxes serve critical needs beyond hurricane response, and effective inventory management ensures these supplies never go to waste. Organizations can rotate their mass disaster relief supplies into individual crisis response on an ongoing basis, maintaining fresh inventory while serving year-round needs:

- Sudden homelessness situations

- Individual families in crisis who need food that requires no preparation

- Emergency distributions at agencies that serve walk-in clients

This dual-purpose functionality makes emergency preparedness investments cost-effective year-round, not just during hurricane season. Rather than stockpiling supplies that sit unused, food banks can maintain active emergency inventory that serves both large-scale disasters and individual crises.

Federal Support: Supplemental, Not Primary

While federal disaster response provides important support, food banks cannot wait for federal coordination to begin operations. As Joe McKinney’s experience demonstrates, effective disaster response requires immediate action using existing resources and relationships, with federal support serving as supplemental assistance that arrives later in the process.

Federal agencies may provide bulk supplies, but these often require local processing, repackaging, and distribution through established food bank networks. The heavy lifting of disaster food relief—understanding local needs, coordinating volunteers, managing logistics—remains with local organizations who know their communities best.

Government Integration: Beyond Your Own Plan

“In addition to hardening their own disaster relief plans, food banks need to coordinate with state and city government disaster relief planning. We’ve learned that there are many pop-up organizations that receive funding through counties or cities—funding that can’t be directly allocated to food banks. These organizations do relief work for a limited time, then they stop operations. Meanwhile, we’re here before, during, and after disasters. Proactive coordination with government agencies sets you up for strategic partnerships rather than reactive scrambling when decisions about hunger relief get made at the moment,” explains Kristi Rose.

This creates coordination challenges when temporary relief organizations receive funding that bypasses established food banks, operate for limited periods, then disappear—leaving food banks to absorb the demand they were temporarily serving.

Successful disaster preparedness requires food banks to:

- Participate in county and city disaster planning committees

- Understand local emergency management funding flows

- Establish formal roles in government disaster response plans

- Plan for handoffs when temporary relief organizations end operations

Technology Infrastructure: Cloud vs. On-Premise

One of MANNA’s most costly losses wasn’t visible: their on-premise inventory management system. This technology choice, common among smaller food banks, meant complete dat90pp-a loss until the technology team was able to access their backup and weeks of operating with manual tracking systems.

Food banks should audit their technology infrastructure for disaster resilience: Are critical systems hosted in the cloud? Can staff access essential data remotely? Do backup systems exist for tracking donations and distributions during power outages?

Beyond Food Banks: Direct Community Partners

Emergency food distribution increasingly involves organizations beyond traditional food banks:

- Churches and faith-based organizations conducting emergency distributions

- Community centers serving as emergency meal sites

- Schools providing emergency food packages to families

- Corporate partners conducting emergency employee assistance

Each type of organization has different capabilities, storage capacity, and distribution methods—requiring flexible approaches to emergency food supply.

Recent disaster response experiences have highlighted the critical role that community-based organizations play in reaching populations that traditional food banks may not effectively serve. Many of these organizations have deep community trust and can operate in areas where formal relief agencies face barriers.

However, they often lack established relationships with food suppliers and may not understand emergency food specifications. Connecting these organizations into professional food supply chains before disasters strike—rather than scrambling to build relationships during crisis—significantly improves overall community resilience.

The Network That Never Sleeps: Building Resilient Communities

Every disaster reminds us that food relief isn’t just about the visible response—food banks, volunteers, and emergency distributions. Success depends on an invisible network of relationships, supply chain expertise, and institutional knowledge built during calm periods and activated during a crisis.

- The companies that can fulfill emergency orders in days rather than weeks.

- The vendors who prioritize disaster relief shipments.

- The teams that work around the clock when communities are in crisis.

- The logistics providers who find ways to deliver supplies to areas that no longer appear on standard maps.

This network represents more than emergency response capability—it’s community resilience built through relationships, refined through experience, and activated when everything else fails.

Key Takeaways for Disaster Relief Organizations:

Preparation Phase:

- Maintain 5-7 days of emergency inventory to bridge supply gaps

- Establish a designated disaster relief committee with one person from each department pre-assigned for crisis response

- Develop authentic mutual aid agreements with neighboring food banks, not just informal relationships

- Build relationships with emergency food suppliers, trucking companies, and alternative facilities before disaster strikes

- Stock foods that require no preparation, including basic tools like can openers

- Ensure critical technology systems (inventory management, communications) are cloud-based

- Participate in county and city disaster response planning, don’t just create your own plan

- Identify potential cross-sector partners (Habitat for Humanity, corporate volunteer programs, etc.) whose missions align

Response Phase:

- Have a rainy day fund available for use before donations flow. Be prepared to act immediately without waiting for funding authorization—donations typically follow decisive action

- Understand that disaster food relief is regional, not just local—prepare for displaced populations

- Coordinate with neighboring organizations to share capacity and resources

- Plan for sustained operations over months, not just immediate response—the scale and duration will surprise you

- Prioritize suppliers who can fulfill emergency orders rapidly, especially those with regional partnerships

- Simplify tracking systems when technology fails—focus on “trucks in, people served” metrics during crisis

- Guarantee staff financial security and flexibility to enable them to focus on both personal recovery and organizational mission

Recovery Phase:

- Provide extended flexibility for staff dealing with child care gaps, FEMA, insurance, and contractor appointments

- Understand that staff recovery phases differ from organizational recovery phases

- Set clear boundaries between emergency response mode and sustainable operations—staff cannot work crisis hours indefinitely

- Plan for coordination with temporary relief organizations and their eventual departure

- Transition from emergency foods to normal food assistance as infrastructure rebuilds

- Document lessons learned and update disaster plans based on actual experience

- Maintain emergency supplier relationships for ongoing individual emergencies

Questions for Your Organization:

- Do you have a designated disaster relief committee with pre-assigned roles from each department?

- Have you established authentic mutual aid agreements with neighboring food banks and community partners?

- Do you have relationships with emergency food suppliers who can fulfill orders rapidly? (Industry standard is 2-3 weeks; emergency-focused suppliers may offer 5-day fulfillment)

- Have you cultivated relationships with suppliers who have regional distribution or mixing centers who demonstrate a willingness and ability to expedite during disasters?

- Does your emergency food inventory reflect actual needs (ready-to-eat foods, including tools, long shelf life)?

- Do you have 5 days of disaster relief supplies ready to distribute? If so, do you have a rotation system to prevent waste?

- Are you prepared to act immediately without waiting for funding authorization, and do you have financial reserves to support the initial response?

- Have you identified alternative facilities (like convention centers) and logistics partners for scaled operations?

- Do you have corporate sponsors committed to supporting dedicated disaster relief inventory?

- Are your critical technology systems (inventory management, communications) cloud-based and accessible remotely?

- Have you participated in county and city disaster response planning, or do you only have your own internal plan?

- Do you have designated staff financial security and flexibility policies for extended crisis operations?

Download this Disaster Preparedness Checklist as a PDF worksheet to share with your team, your board, and to add to your disaster preparedness plan.

About Value Added Food Sales: For over 30 years, VAFS has served food banks, pantries, and disaster relief organizations across the United States, focused solely on serving non-profit hunger relief organizations. VAFS maintains mixing centers, including some co-located with major food banks, such as Second Harvest Food Bank of Metrolina in Charlotte, providing operational insight into food bank crisis management for disaster response planning.

The company’s disaster relief expertise was established during Hurricane Katrina, when VAFS contributed to the development of industry standards for emergency food distribution that remain in use today.

VAFS’s network of mixing centers provides reliable fulfillment during disasters, regardless of regional impact, thanks to its nationwide footprint. Each mixing center offers STANDARD lead times of just 5 business days for order fulfillment, with expedited shipments possible for emergency and disaster response needs. Established relationships with 110+ manufacturing partners allow VAFS to fulfill and expedite orders when traditional supply chains fail, helping you to maintain operations during critical response periods